What Renzo Piano taught us about light

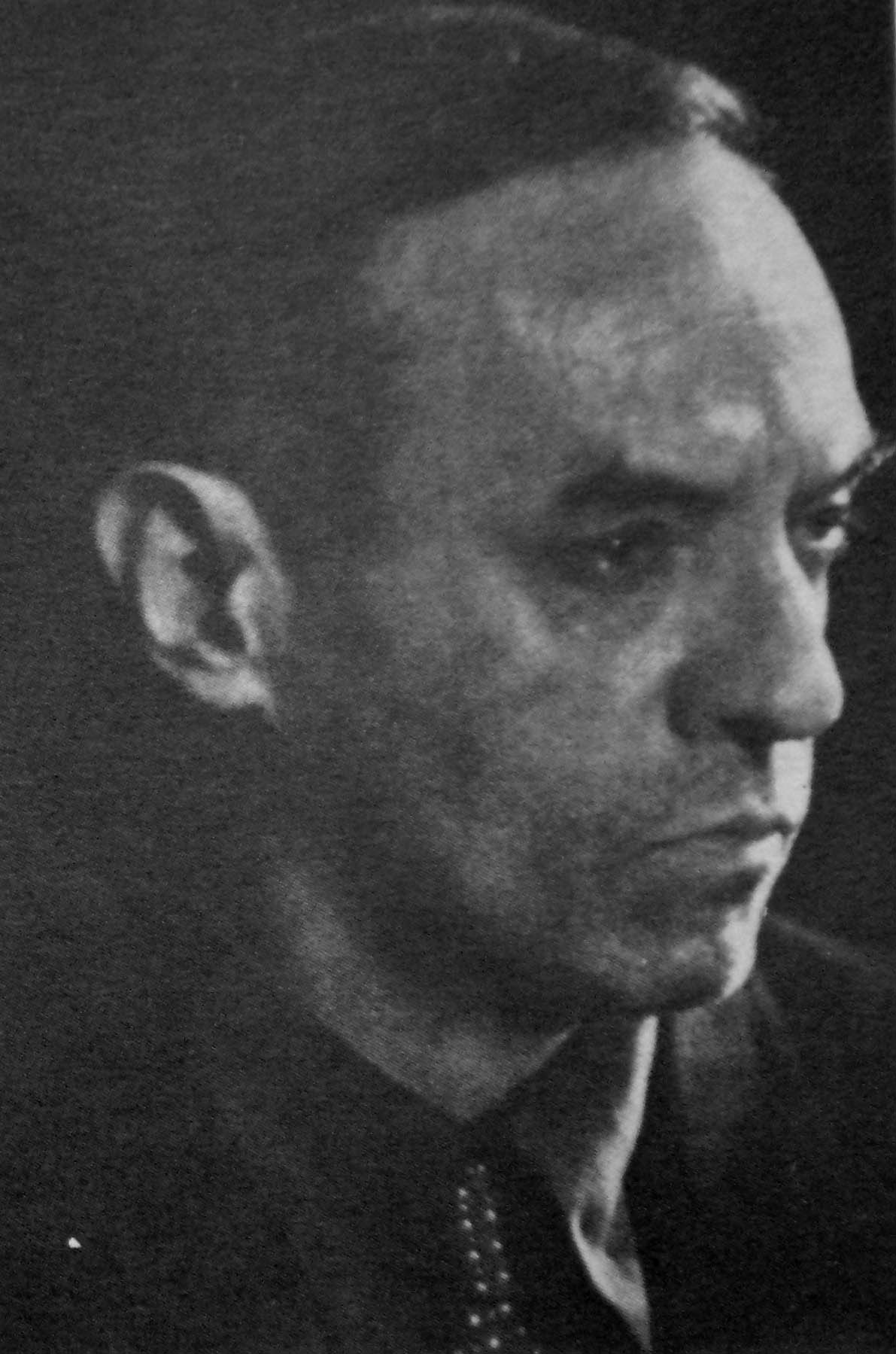

Some people are born to change the path of their industries, and Renzo Piano is one such person. Born in Italy, Piano has become known as one of the most masterful and respected architects in the world, thanks to his many iconic projects, including not least the Georges Pompidou Center in Paris.

In this article, we will delve further into what makes Piano an icon of architecture and how he uses one resource in particular — light.

The history

To understand how Renzo Piano got to where he is today, we need to take a look back at his humble beginnings. The son of a builder, his big break came in the 1960s when he worked as an assistant to Le Ricolais in the architecture department of the University of Pennsylvania. However, it wasn’t Ricolais who afforded him a significant opportunity — it was Louis Kahn.

After meeting Piano at the home of Ricolais, Kahn was searching for a designer to help with drawings for the Olivetti-Underwood Factory. In fewer than seven days, Piano was hired and worked intermittently with Kahn before starting his own firm.

The Kahn effect

Although Kahn and Piano eventually parted ways, the impact of Kahn’s teaching is easy to spot. From the Whitney Museum to Piano’s Pavilion at the Kimbell, anyone can glean an insight into Piano’s methods. Take the expansion of the Harvard Art Museums as an example. Using a glass-filled atrium that extended the courtyard five levels upward, he brought together three museums and made them feel as one.

Light-filled volumes and the creation of urban views through glass walls are just two of the lessons Piano learned from Kahn. How do we know this? It’s evident in Kahn’s work and his writings in his book, Light Is the Theme. By slanting sunlight through bands and oculus, Kahn crafted a luminous effect at Trenton Bath House. The use of sunlight falling through gaps is also evident in the vaults of his Kimbell Building. Many believe the Kimbell’s vaults are merely the foundation of the bathhouses in Trenton, but squared.

Piano’s evolution

Of course, every innovator takes his craft to a new level, and Piano was no different. While remnants of his past are still evident in his work — with slanted walls and sharp angles — there’s no doubt Piano has mastered new techniques. One is the conversation that can be had between two adjacent buildings. While lots of architects don’t think about the adjoining structures and gaps next to their buildings, Piano ensures they are carefully considered.

An excellent example of how he took this one level further than Kahn is with his Pavilion at Kimbell. Previously, visitors at the Kimbell Museum – built by Kahn – couldn’t experience the beauty of the area as a whole. Arriving on the lower floor at the building’s rear, the porticos and pools at front were omitted from view. Piano, on the other hand, rectified this by incorporating an expansive area of lawn and trees with an exquisite view of the museum’s facade. A glass elevator or grand stairway ensures natural light is at the forefront, even if visitors come from the underground parking garage.

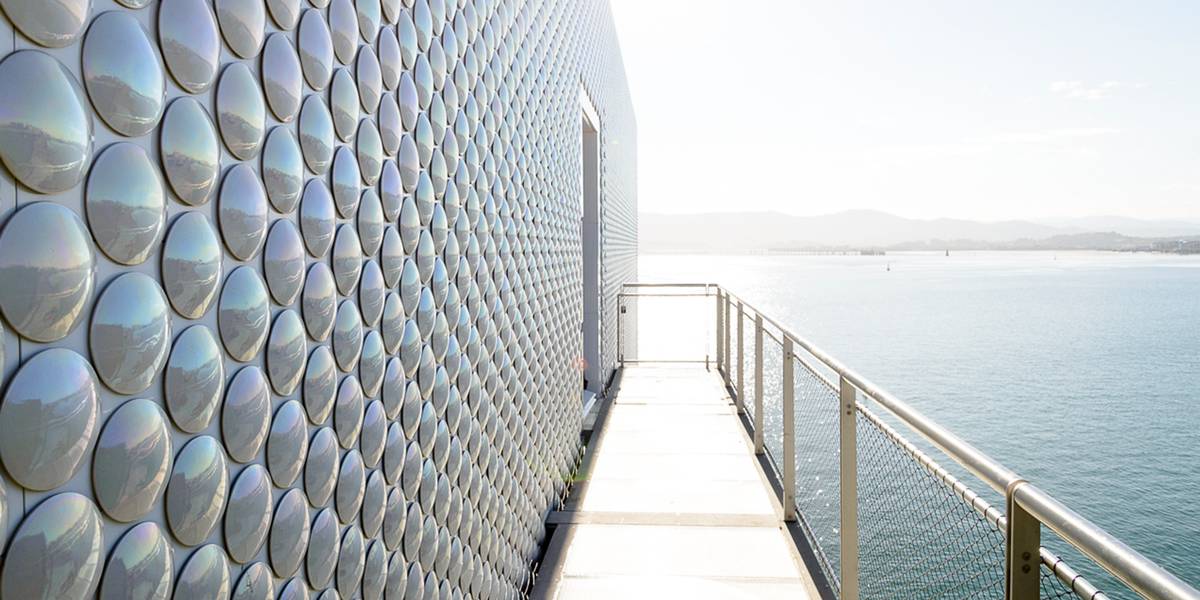

The conversation between buildings doesn’t end there in Piano’s work. Staying on the subject of his Pavilion, the fact it exists as a separate entity ensures it feels airy and spacious. The buildings that comprise Piano’s Pavilion are also connected by two glass passageways, drawing in light from every possible source.

Original light sources are a permanent fixture of Piano’s designs. In the Kimbell Pavilion, materials of all kinds are used to give the perception of dispersed light. Kahn indeed used this effect a lot; however, Piano exploited shiny, reflective surfaces to create a modern equivalent. As well as glass and metal, the smooth concrete and titanium create a clerestory band of light that filters through and is simultaneously evenly distributed. The wooden beams mixed with white columns add depth as they contrast with Piano’s usual light sources. Instead, the canopy shades light.

Respecting the artefacts

Probably the feature that sets Piano apart from any other architect is his respect for the art on display in his buildings. Rather than creating a light-filled atmosphere that drowns out paintings and sculptures, he seeks to embrace them in the architecture. Movable wall panels not only allow for flexibility and the changing of angles, but they also keep any display in the viewer’s eye line.

Where possible, light is modulated so that objects can be viewed in all their glory. And, when it is hard to pull in natural light, he positions artefacts that don’t require illuminating in these spaces.

It would be easy for Piano to argue that his buildings are their own entity and lure in visitors themselves. Still, he has a holistic approach to architecture that enhances the surrounding areas as well as his designs. The view across the gallery floor at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York is a prime example where visitors can see across the massive space.

Renzo Piano, the Architect of Light

If you want an insight into the way Piano thinks, you need to watch the documentary, “Renzo Piano, the Architect of Light.” Created by the renowned Spanish director Carlos Saura, Piano talks about how light is the “most important building material, which is connected to the water.” He also points out how it’s the patient nature of his designs that make them unique. Like looking in the dark, you have to let your eyes adjust when viewing his architecture.

Piano’s Legacy

By understanding the ways in which Renzo Piano used light in his designs, it’s not hard to see why he has crafted some of the most beautiful buildings in the world, from the The Shard in London to the New York Times Building in Manhattan. He is the true master of light and one we take great inspiration from here at XUL.

Image Courtesy Chicago Film Festival